In a series of marriages and conquests, a succession of Burgundian dukes expanded their original territory by adding to it a series of fiefdoms, including the Seventeen Provinces. Although Burgundy itself had been lost to France in 1477, the Burgundian Netherlands were still intact when Charles V was born in Ghent in 1500. He was raised in the Netherlands and spoke all the European languages fluently. Subsequently, in 1516, he inherited several titles, including the combined kingdoms of Aragon and Castile and León, which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the Americas, became ruler of the Habsburg empire, with the title Holy Roman Emperor so virtually all of the Netherlands had been incorporated into the Habsburg domains by the early 1540s.

Flanders had long been a very wealthy region, coveted by French kings and, along with other regions of the Netherlands had also grown wealthy. Charles V’s empire had become a worldwide empire with large American and European territories. Control and defense of these were hampered by the disparity of the territories and huge length of the empire’s borders. This large realm was almost continuously at war with its neighbors , most notably against France and against the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean Sea. Further wars were fought against Protestant princes in Germany. The Dutch paid heavy taxes to fund these wars, but perceived them as unnecessary and sometimes downright harmful, because they were directed against their most important trading partners.

Already in 1566 William I of Orange had asked for Ottoman support. As Suleiman the Magnificent claimed that he felt religiously closer to the Protestants, “since they did not worship idols, believed in one God and fought against the Pope and Emperor” he supported the Dutch together with the French and the English, as well as generally support Protestants as a way to counter Habsburg attempts at supremacy in Europe.

In an effort to finance his troops, Alba had proposed to the States that a sales tax be introduced, the “Tenth Penny”. This proposal was rejected by the States, and a compromise was subsequently agreed upon, but Alba decided to press forward with the collection of the Tenth Penny regardless of the States’ opposition. This aroused strong protest from both Catholics and Protestants, and support for the rebels grew once more and was fanned by a large group of refugees who had fled the country during Alba’s rule.

introduced, the “Tenth Penny”. This proposal was rejected by the States, and a compromise was subsequently agreed upon, but Alba decided to press forward with the collection of the Tenth Penny regardless of the States’ opposition. This aroused strong protest from both Catholics and Protestants, and support for the rebels grew once more and was fanned by a large group of refugees who had fled the country during Alba’s rule.

The Catholic Reformation took place within the Roman Catholic Church during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Also known as the Counter Reformation, many historians prefer not to use this term because it suggests that changes within the church were simply a reaction to Protestantism. Popes, cardinals, bishops, and priests had become corrupt. Neglecting their responsibilities as religious leaders, they pursued their own personal advancement by the sale of indulgences. The church accumulated more property and wealth than kings and princes.

During the fourteenth century the church faced a serious crisis that hastened the need for reform. In 1307, following a power struggle among cardinals, the papacy was moved to Avignon, France, where it remained for seventy years. This period was known as the Babylonian captivity. When the cardinals had another confrontation that caused a deep split in the church, and soon there were two popes, one in Avignon and one in Rome. At one point there were even three popes vying for control. This period was called the Great Schism. It ended in 1417 with the Council of Constance, a meeting of church officials and heads of European states.

Once the papacy was permanently returned to Rome, deep corruption and abuse of power became even more obvious. All the heads of the church were members of ruthless Italian families such as the Medicis in Florence and the Sforzas in Milan, who profited from controlling the papacy. They operated complex schemes and appointed family members to high church positions. Cardinals had luxurious homes, bishops did not reside in their districts, and priests were poorly educated.

Another crisis occurred in May 1527, when soldiers in the army of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked the city of Rome. For several months they terrorized citizens and looted and burned buildings. Pope Clement VII fled to a castle, where he was a prisoner until he paid for his release. The siege has often been called the “German Fury” because the majority of the marauding soldiers were German Lutherans. Even the pope’s supporters agreed that the moral failings of the clergy helped to bring on the catastrophe. Soon pamphlets were circulating around Rome, proclaiming that prophesies of punishment and doom were being fulfilled. One such prophesy was a blade shaped comet, which was supposedly a sign that disaster would take place. The sack of Rome also gave renewed life to reforming preachers, who warned that Rome would someday have to pay for the sins and corruption of the church.

During the 16th century, Protestantism rapidly gained ground in northern Europe. So that by the 1560s, the Protestant community had become a significant influence in the Netherlands, in a society where trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Nevertheless, Charles V, and, from 1555, his successor Philip II, felt it was their duty to defeat Protestantism, which was considered a heresy by the Catholic Church and a threat to the stability of the whole hierarchical political system. On the other hand, the intensely moralistic Dutch Protestants insisted their Biblical theology, sincere piety and humble lifestyle was morally superior to the luxurious habits and superficial religiosity of the ecclesiastical nobility. The harsh measures of suppression led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where the local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands once more a Catholic region. Although failing in his attempts to introduce the Spanish Inquisition directly, the Inquisition of the Netherlands was nevertheless sufficiently harsh and arbitrary in nature to provoke fervent dislike.

By the 15th century, Brussels had thus become the de facto capital of the Seventeen Provinces. Dating back to the Middle Ages, the districts of the Netherlands, represented by its nobility and the wealthy city dwelling merchants, still had a large measure of autonomy in appointing its administrators. Charles V and Philip II set out to improve the management of the empire by increasing the authority of the central government in matters like law and taxes, a policy which caused suspicion both among the the merchant class. Under the governorship of Mary of Hungary, traditional power had for a large part been taken away both from the stadtholders of the provinces and from the high noblemen, who had been replaced by professional jurists in the Council of State.

Antwerp played an important role as a distribution centre in northern Europe. After 1591, however, the Portuguese used an international syndicate of the German Fuggers and Welsers, and Spanish and Italian firms, that used Hamburg as the northern staple port to distribute their goods, thereby cutting Dutch merchants out of the trade. At the same time, the Portuguese trade system was unable to increase supply to satisfy growing demand for pepper. Demand for spices was relatively inelastic, and therefore each lag in the supply of pepper caused a sharp rise in pepper prices.

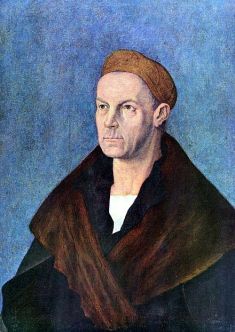

The founder of the family was Johann Fugger, his son, called Hans, settled in Augsburg, and the first reference to the Fugger family there is the tax register of 1367 ; by 1396 he was ranked high in the list of taxpayers, adding the business of a merchant to that of a weaver. Hans Fugger’s younger son, Jakob the Elder, founded another branch of the family. This branch progressed more steadily and they became master weavers, merchants, and an alderman. His fortune progressed, and by 1461, he was the twelfth richest man in Augsburg. He died in 1469.

With the help of their brother in Rome, Markus, Ulrich and his brother George handled remittances to the papal court of monies for the sale of indulgences and the procuring of church benefices. From 1508 to 1515 they leased the Roman mint and when the Fuggers made their first loan to the Archduke Sigismund in 1487, they took as security an interest in silver and copper mines in the Tirol. This was the beginning of an extensive family involvement in mining and precious metals. The Fuggers also participated in mining operations in Silesia, and owned copper mines in Hungary. Their trade in spices, wool, and silk extended to all parts of Europe.

Ulrich’s youngest brother Jakob Fugger, born in 1459, was to become the most famous member of the dynasty. In 1498 he married Sibylla Artzt, the daughter of an eminent Grand Burgher of Augsburg which gave Jakob the opportunity to become a Grand Burgher of Augsburg and later allowed him to pursue a seat on the city council (Stadtrat) of Augsburg. He was elevated to the nobility of the Holy Roman Empire in May 1511, created Imperial Count in 1514, and in 1519 led a consortium of German and Italian businessmen that loaned Charles V 850,000 florins [about 95,625 oz of gold] to procure his election as Holy Roman Emperor over Francis I of France. The Fuggers’ contribution was 543,000 florins.

At the height of his power Jakob Fugger was sharply criticized by his contemporaries, especially Martin Luther, for selling indulgences and benefices and urging the Pope to rescind or amend the prohibition on the levying of interest. The imperial fiscal and governmental authorities in Nuremberg brought action against him and other merchants in an attempt to halt their monopolistic tendencies. In 1511, Jakob deposited 15,000 florins as an endowment for some almshouses. In 1514, he bought up part of Augsburg and in 1516 came to an agreement to provide almshouses for needy citizens. By 1523, 52 houses had been built, and the Fuggerei had come into existence. It is still used today.

A number of Dutchmen obtained first hand knowledge of the “secret” Portuguese trade routes and practices, thereby providing opportunity for a four-ship exploratory expedition in 1595 to Banten, the main pepper port of West Java, [and the derivation of the name of a small variety of poultry, Bantam] where they clashed with both the Portuguese and indigenous Indonesians. Houtman’s expedition then sailed east along the north coast of Java, losing twelve crew to a Javanese attack at Sidayu and killing a local ruler in Madura. Half the crew were lost before the expedition made it back to the Netherlands the following year, but with enough spices to make a considerable profit.

In 1598, an increasing number of fleets were sent out by competing merchant groups from around the Netherlands. Some fleets were lost, but most were successful, with some voyages producing high profits. In March 1599, a fleet of eight ships under Jacob van Neck was the first Dutch fleet to reach the ‘Spice Islands’, the source of pepper, cutting out the Javanese middlemen, returning to Europe where they sold their cargo at a 400% profit. In 1600, the Dutch joined forces with the Muslim Hituese on Ambon Island in an anti-Portuguese alliance, in return for which the Dutch were given the sole right to purchase spices. East of Solor, on the island of Timor, Dutch advances were halted by an autonomous and powerful group of Portuguese Eurasians called the Topasses. They remained in control of the sandalwood trade and their resistance lasted throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, causing Timor to remain under the Portuguese sphere of control.

anti-Portuguese alliance, in return for which the Dutch were given the sole right to purchase spices. East of Solor, on the island of Timor, Dutch advances were halted by an autonomous and powerful group of Portuguese Eurasians called the Topasses. They remained in control of the sandalwood trade and their resistance lasted throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, causing Timor to remain under the Portuguese sphere of control.

At the time, it was customary for a company to be set up only for the duration of a single voyage and to be liquidated upon the return of the fleet. Investment in these expeditions was a very high-risk venture, not only because of the usual dangers of piracy, disease and shipwreck, but also because the interplay of inelastic demand and elastic supply of spices could make prices tumble at just the wrong moment, thereby ruining prospects of profitability. To manage such risk the English had been the first to adopt the approach of bundling their resources into a monopoly enterprise, the English East India Company, thereby threatening their Dutch competitors with ruin.

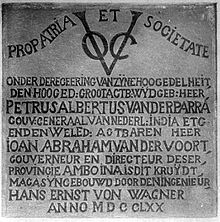

In 1602, the Dutch government followed suit, sponsoring the creation of a single “United East Indies Company” [VoC] that was also granted monopoly over the Asian trade. With a capital of 6.4 million guilders, the charter of the new company empowered it to build forts, maintain armies, and conclude treaties with Asian rulers. It provided for a venture that would continue for 21 years, with a financial accounting only at the end of each decade.In February 1603, the Company seized the Santa Catarina, a 1500-ton Portuguese merchant carrack, off the coast of Singapore. She was such a rich prize that her sale proceeds increased the capital of the VOC by more than 50%.

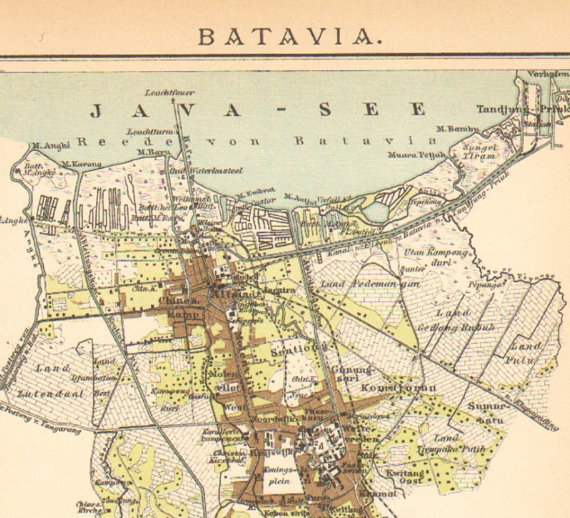

Also in 1603 the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Banten, and in 1611 another was established at Jayakarta [later “Batavia” and then “Jakarta”]. In 1610, the VOC established the post of Governor General to more firmly control their affairs in Asia. To advise and control the risk of despotic Governors General, a Council of the Indies was created. The Governor General effectively became the main administrator of the VOC’s activities in Asia, although the Heeren XVII, a body of 17 shareholders representing different chambers, continued to officially have overall control.

VOC headquarters were located in Ambon during the tenures of the first three Governors General, but it was not a satisfactory location. Although it was at the centre of the spice production areas, it was far from the Asian trade routes and other VOC areas of activity ranging from Africa to India to Japan. A location in the west of the archipelago was thus sought. The Straits of Malacca were strategic but had become dangerous following the Portuguese conquest, and the first permanent VOC settlement in Banten was controlled by a powerful local ruler and subject to stiff competition from Chinese and English traders.

In 1604, a second English East India Company voyage commanded by Sir Henry Middleton reached the islands of Banda, where they encountered severe VOC hostility, sparking Anglo-Dutch competition for access to spices. From 1611 the English established trading posts throughout the spice islands which threatened Dutch ambitions for a monopoly on East Indies trade. Diplomatic agreements ended with a notorious but disputed incident known as the ‘Amboyna massacre‘, where ten Englishmen were arrested, tried and beheaded for conspiracy against the Dutch government. Although this caused outrage in Europe and a diplomatic crisis, the English quietly withdrew from most of their Indonesian activities [except trading in Banten] and focused on other Asian interests.

In 1619 Jan Pieterszoon Coen was appointed Governor-General of the VOC: he saw the possibility of the VOC becoming an Asian power, both political and economic, so, backed by a force of nineteen ships, he stormed Jayakarta, driving out the Banten forces; and from the ashes established Batavia as the VOC headquarters. In the 1620’s almost the entire native population of the Banda Islands was driven away, starved to death, or killed in an attempt to replace them with Dutch plantations to grow cloves and nutmeg for export. Coen hoped to settle large numbers of Dutch colonists in the East Indies, but implementation of this policy never materialised, mainly because very few Dutch were willing to emigrate to Asia.

Another of Coen’s ventures was more successful. A major problem in the European trade with Asia at the time was that the Europeans could offer few goods that Asian consumers wanted, except silver and gold. European traders therefore had to pay for spices with the precious metals, which were in short supply in Europe, except for Spain and Portugal. The Dutch and English had to obtain it by creating a trade surplus with other European countries. Coen discovered the obvious solution for the problem: to start an intra-Asiatic trade system, whose profits could be used to finance the spice trade with Europe. In the long run this obviated the need for exports of precious metals from Europe.

![voc[1]](https://forgeofempiressite.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/voc1.jpg?w=656)

The VOC traded throughout Asia. Ships coming into Batavia from the Netherlands carried supplies for VOC settlements in Asia. Silver and copper from Japan were used to trade with India and China for silk, cotton, porcelain, and textiles. These products were either traded within Asia for the coveted spices or brought back to Europe. The VOC was also instrumental in introducing European ideas and technology to Asia. The Company supported Christian missionaries and traded modern technology with China and Japan.

The VOC trade post off the coast of Nagasaki, was for more than two hundred years the only place where Europeans were permitted to trade with Japan. When the VOC tried military force on the Ming dynasty to open up to Dutch trade, the Chinese defeated the Dutch and forced the VOC to abandon their port for Taiwan. The Vietnamese Nguyen Lords defeated the VOC in a 1643 battle during the Trịnh–Nguyễn War, blowing up a Dutch ship. The Cambodians defeated the VOC at a battle on the Mekong.

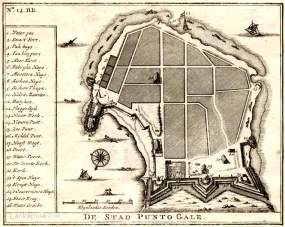

In 1640, the VOC obtained the port of Galle, Ceylon, from the Portuguese and broke the latter’s monopoly of the cinnamon trade. In 1658, it laid siege to Colombo, which was captured with the help of King Rajasinghe II of Kandy. By 1659, the Portuguese had been expelled from the coastal regions, which were then occupied by the VOC, securing for it the monopoly over cinnamon. To prevent the Portuguese or the English from ever recapturing Sri Lanka, the VOC went on to conquer the entire Malabar Coast from the Portuguese, almost entirely driving them from the west coast of India. When news of a peace agreement between Portugal and the Netherlands reached Asia in 1663, Goa was the only remaining Portuguese city on the west coast.

latter’s monopoly of the cinnamon trade. In 1658, it laid siege to Colombo, which was captured with the help of King Rajasinghe II of Kandy. By 1659, the Portuguese had been expelled from the coastal regions, which were then occupied by the VOC, securing for it the monopoly over cinnamon. To prevent the Portuguese or the English from ever recapturing Sri Lanka, the VOC went on to conquer the entire Malabar Coast from the Portuguese, almost entirely driving them from the west coast of India. When news of a peace agreement between Portugal and the Netherlands reached Asia in 1663, Goa was the only remaining Portuguese city on the west coast.

In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck established an outpost at the Cape of Good Hope to re-supply VOC ships on their journey to East Asia. This post later became a full-fledged colony, the Cape Colony, when more Dutch and other Europeans started to settle there. VOC trading posts were also established in Persia. Bengal, Malacca, Siam, Canton, Formosa, as well as the Malabar and Coromandel coasts in India. In 1663, the VOC signed “Painan Treaty” with several local lords in the Painan area that were revolting against the Aceh Sultanate. The treaty resolved the VOC to build a trading post in the area and eventually monopolize the gold trade there.

In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck established an outpost at the Cape of Good Hope to re-supply VOC ships on their journey to East Asia. This post later became a full-fledged colony, the Cape Colony, when more Dutch and other Europeans started to settle there. VOC trading posts were also established in Persia. Bengal, Malacca, Siam, Canton, Formosa, as well as the Malabar and Coromandel coasts in India. In 1663, the VOC signed “Painan Treaty” with several local lords in the Painan area that were revolting against the Aceh Sultanate. The treaty resolved the VOC to build a trading post in the area and eventually monopolize the gold trade there.

By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen, with over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and a dividend payment of 40% on the original investment. Around the world and especially in English-speaking countries, the VOC is widely known as the “Dutch East India Company”. The name ‘Dutch East India Company’ is used to make a distinction with the British and other East Indian companies . The abbreviation “VOC” stands for “Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie” in Dutch.

The VOC monogram was possibly the first globally-recognized corporate logo. It appeared on various corporate items, such as cannon and coins. The first letter of the hometown of the chamber conducting the operation was placed on top. An Australian vintner has used the VOC logo since the late 20th century, having re-registered the company’s name for the purpose.

The VOC monogram was possibly the first globally-recognized corporate logo. It appeared on various corporate items, such as cannon and coins. The first letter of the hometown of the chamber conducting the operation was placed on top. An Australian vintner has used the VOC logo since the late 20th century, having re-registered the company’s name for the purpose.

Netherlands Indies

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Netherlands_Indies_gulden

A number of forms of payment were found throughout the archipelago prior to European contact. Stamped gold and silver masa and kupang date from the 9th century, with later coins substantially debased, with 13th century silver masa containing only copper, while gold coins were very light. It is possible that this reflected a move towards the use of lower value coins for every day transactions.

The rise of the Majapahit empire from the 13th century saw the masa disappear from  use, replaced with the ‘picis’, or copper Chinese cash in the 14th century, which had been produced in vast numbers in China, and were kept in strings of 100 or 1000 coins. 14th century documentation shows the cash coins in widespread use, which spread to nearby islands including Sumatra , although not the Islamic Aceh, which minted its own Arabic gold coins.

use, replaced with the ‘picis’, or copper Chinese cash in the 14th century, which had been produced in vast numbers in China, and were kept in strings of 100 or 1000 coins. 14th century documentation shows the cash coins in widespread use, which spread to nearby islands including Sumatra , although not the Islamic Aceh, which minted its own Arabic gold coins.

As standard circular coins were developed following the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang, the most common formation was the round-shaped copper coin with a square or circular hole in the center, the prototypical cash. The hole enabled the coins to be strung together to create higher denominations, as was frequently done due to the coin’s low value. The number of coins in a string of cash varied over time and place but was nominally 1000. A string of 1000 cash was supposed to be equal in value to one tael of pure silver. A string of cash was divided into ten sections of 100 cash each. Local custom allowed the person who put the string together to take a cash or a few from each hundred for his effort . Thus an ounce of silver could exchange for 970 in one city and 990 in the next. In some places in the North of China short of currency the custom counted one cash as two and fewer than 500 cash would be exchanged for an ounce of silver. A string of cash weighed over ten pounds and was generally carried over the shoulder.

Trade with China was interrupted for substantial portions of the next two centuries, and so lighter copies were made by local Chinese merchants out of locally available lead or tin rather than the more desirable copper, which needed to come from China. In the Islamic Sultanate of Palembang, these coins became, from the 17th century, the ‘pitis’, a holed coin with Arabic writing.

European trade with the Indies began in the 16th century, with the Spanish eight real  coin, or Spanish Dollar, the predominant world trade coin, used in Portuguese expeditions to the East to bring valuable spices back to Europe. Chinese and other Asian traders were also using silver coins including the Indian Rupee and Eight Real. The low-valued picis had wildly fluctuating value, but were worth around 10,000 lead picis to the piece of eight around the turn of the 17th century. Due to lack of supply of the genuine Chinese copper picis, they were worth six times as much as the lead coin by this time.

coin, or Spanish Dollar, the predominant world trade coin, used in Portuguese expeditions to the East to bring valuable spices back to Europe. Chinese and other Asian traders were also using silver coins including the Indian Rupee and Eight Real. The low-valued picis had wildly fluctuating value, but were worth around 10,000 lead picis to the piece of eight around the turn of the 17th century. Due to lack of supply of the genuine Chinese copper picis, they were worth six times as much as the lead coin by this time.

Trade companies in two provinces of the Netherlands began trading expeditions to the Indies in the late 16th century, and were authorised to issue their own trade coins for use on these expeditions: the United Amsterdam Company in 1601 and the Middelburg Company in 1602. The 1601 coin was the first trade dollar issued by any European power in the East, but the unfamiliar coins were rejected in favor of the well-known coins produced by Spain and its possessions, which were accepted all over the world and remained the preferred trade coin in the Indies until the 19th century.

In 1602, the United East India Company (VOC) was formed from six trading companies in the Netherlands, and granted a trade monopoly over the Indies. In 1619 the Company established its capital at Batavia. The rijksdaalder, with 25.7 g silver weight, was declared the Dutch national coin in 1606, and valued at 47 stuivers, increased to 48 stuivers in 1608. In practice, the rijksdaalder proved less desirable than the better-known Spanish 8 Real coin, and as the rijksdaalder contained more silver, they disappeared from circulation. As a result, the VOC shipped the Spanish coin in large quantities, and it was the standard large coin of the Indies, used in official transactions, and given the same 48 stuiver value as the rijksdaalder.

In 1602, the United East India Company (VOC) was formed from six trading companies in the Netherlands, and granted a trade monopoly over the Indies. In 1619 the Company established its capital at Batavia. The rijksdaalder, with 25.7 g silver weight, was declared the Dutch national coin in 1606, and valued at 47 stuivers, increased to 48 stuivers in 1608. In practice, the rijksdaalder proved less desirable than the better-known Spanish 8 Real coin, and as the rijksdaalder contained more silver, they disappeared from circulation. As a result, the VOC shipped the Spanish coin in large quantities, and it was the standard large coin of the Indies, used in official transactions, and given the same 48 stuiver value as the rijksdaalder.

Small change intended for local use did not need to be accepted outside the Indies, so Dutch silver dubbeltjes and schillings were imported. In 1644 the VOC instructed a Chinese resident of Batavia named Conjok to mint copper coinage in denominations of a half and quarter stuiver to address the shortage of low denomination money. The first VOC silver coins were issued in 1645 by Dutch goldsmith Jan Ferman along with Conjok known as the Batavian Crown. These were made from Japanese silver bars as an emergency measure to address the lack of large silver coins due to the locals selling the large Dutch silver coins to Chinese traders for a profit. Due to counterfeiting, the coins were withdrawn two years later, in 1647. These coins, the first to bear the VOC monogram, and the last until 1724, are now very scarce.

To subdivide the Indies stuiver, in 1658 an official issue of the lari known as Tangs—’fish hook’ coins made of copper was attempted. The tang were to be officially stamped to prevent clipping, but this was unsuccessful as the copper proved too hard to work.

The silver larin coinage, which originated in the Persian Gulf, was used extensively from that region around the coast of the Indian Ocean as far as Lanka during the period 17th centuries. Larins used in Lanka were bent into a “fish-hook” shape whereas those of other regions were straight. Larins actually produced in Lanka bore either imitation Persian inscriptions though specimens bearing western inscriptions are reported to have also been produced. Larins of more northerly origin that reached Lanka in the course of trade tended to be bent into “fish-hook” shape when they later served the currency needs of the island. A 17th century larin would weigh about 4.75 grams. It was traditionally tariffed at 5.5 lari to the Spanish colonial piece of eight. Lari is the root of coin denominations used in Georgia and the Maldives.

In addition to the 8 Real, a number of other large coins were in use including the Dutch silver ducat. the Dutch lion thaler and cross thaler and the ducaton. Gold coinage included the Dutch gold ducat, as well as the Japanese koban gold plaque and ichi-bu gold coin, all of which were at various times in the late 17th century subject to countermarking, a measure designed to keep genuine, high-quality coins in use, but which were all ended as the countermarks could also be falsified.

In the last decade of the 17th century, the Indian silver rupee was introduced to the Indies by the Dutch, who initially counter stamped the coins, and valued them at an excessive value. Other late 17th century counter marking efforts included a 1686 initiative to counter stamp imported ducatons (which were thereby given greater value), rijksdaalders and half ducatons. This measure ended in 1692. Another counterstamping measure was of the silver stuiver coins of Zeeland, which were counterstamped from 1687 for a number of years.

The VOC wished to introduce copper coinage, replacing the picis, the supply of which had been interrupted by the Japanese, and began to import Dutch duit in 1724 from the province of Holland. Although two of the Dutch provinces had granted their VOC Companies permission to mint coins in the name of Batavia in 1624, the Dutch Parliament withheld its assent to this, and no such VOC coinage was issued until 1726, when there were two different classes of duits: those circulating in the Netherlands, and those circulating in the Indies. By declaring that only duits bearing the ‘VOC’ monogram would be legal tender in the Indies, the VOC could keep its monopoly on these coins, though the high value of duits relative to their intrinsic worth meant that forgeries were common in the Indies.

Along with the imported duits others were produced under authority of the Company in Java, with one side inscribed ‘DUYT JAVAS [date]’, and the other the same text in Arabic. These coins lacked both VOC monogram and arms. The duit gradually became more popular over the 18th century. Ten million were sent to the Indies in the 1770s alone. They circulated alongside the picis and by 1800 the duit had superseded the inconvenient picis in Java.

The Batavian Mint opened in 1744,with the first product Javan gold ducats or dirhams, valued at four silver rupees, and made of 4.3 g of fine gold, with writing only in Arabic. Double ducats were minted 1746 to 1748 after which minting of the Javan ducat ended, due to counterfeiting. From 1753 imported gold Dutch ducats began to be counter stamped in Batavia with the Arabic letters ‘DJAWA’ a measure designed to discourage private import/export of the coins.

Silver Javan rupee

As the silver Indian rupee was a popular coin locally, a local version of it was issued in 1747, with Arabic text [reading ‘Dirham of the Dutch Company’], and only the date in Roman script, identical in weight to the Surat rupee of the Mughal Empire. The Batavian mint once again struck the silver rupee from 1764 to 1767, but in early 1768 production ceased as enough silver coinage had been produced.

Aside from the numerous varieties of VOC duit, the other major development of 18th century Indies coinage occurred from 1786, when European powers started issuing colonial silver coinage in greater quantity, finally satisfying local demand which led to fluctuating local values between large and small silver coins and between silver and copper. Starting from 1796, the mint in Batavia began to produce heavy ‘copper bonk’ coinage formed from long copper bars imported from Japan. Issued by the Dutch from their East Indies colony in the early 19th century ‘bonk’ coinage was cut from oval or rectangular copper bars known as ‘bonks’ [meaning ‘large piece’ in Dutch] the irregular lozenge shaped bonk coinage was usually stamped with a year and denomination. It was an emergency or stopgap issue designed to quickly and cheaply supply coinage to a colony that was rich with trade yet short on coinage. The reasons for the shortage of coinage in the East Indies were strongly linked to the political upheavals in the parent Netherlands from 1795 through to 1815. Political turmoil in the Netherlands included the end of the Dutch Republic in 1795, the formation and collapse of the French Batavian Republic from 1795 to 1806, and the founding of the French puppet Kingdom of Holland from 1806-1813. This Kingdom ended with the defeat of Napolean at Leipzig in 1813 and was succeeded by the independent Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 which only ceased to exist in 1949.

During the period of the puppet Kingdom of Holland the Netherlands actually lost control of the East Indies Colonies completely to the British in 1810, but Dutch rule was re-established in 1814. One can imagine that during this 20 years of chaos that the supply of coinage to a colony several thousand miles away would have been far from the minds of government officials. Thus the East Indies had to rely on counter stamped coinage of other countries and colonies as well as locally minted currency.

The bonk coinage was made in preference to milled round coinage in times of immediate need because they were much cheaper and easier to make. Manufactured in Batavia they were cut from copper rods which varied greatly in size and were generally imported from Japan. The weights of the coins varied considerably as quality control was poor and the stuiver was continually being de-valued against the Dutch Guilder. Copper bonk coins were minted in 3 distinct periods, under the Batavian Republic, under the Kingdom of Holland, and under the Kingdom of Netherlands. Many varieties existed but generally those minted prior to 1818 displayed the value in a pearled or dotted border on one side and the date in a similar border on the other. Those minted in 1819 displayed the value on one side without a border and the date on the other in a lined rectangle. The coins minted earlier can be quite rare and valuable while the later dates are a little more common.

Batavian Republic

The VOC was nationalised by the Netherlands in 1800, and a Council for Eastern Possessions was established to administer it. The Indies had a great shortage of copper coinage, and so the minting of duits resumed at four mints in the Netherlands. Three of these used old VOC designs with new dates from 1802 to 1806, while the fourth, the designated central mint of the new Republic at Enkhuyzen, bore the inscription ‘INDIA BATAV’ where the VOC monogram had been, and with the arms of the Crowned States instead of the individual province’s arms. These coins were originally intended for use in the Cape of Good Hope, but due to the loss of that colony, where the duit was higher valued, they were sent to the Indies instead.

The Dutch administration was replaced following the British invasion of Java in 1811, and the appointment of Stamford Raffles as Governor-General. Raffles initially re-established the 8 Real as the standard coin, recalling 8.5 million rijksdaalder of banknotes for silver. Subsequently the British minted silver rupees and half rupees, the latter seen as a convenient new denomination for payment, from 1811 to 1817 bearing Javanese and Arabic text and dates, as well as gold half mohurs of 1813–1816, this activity continuing for a couple of years after return to Netherlands authority. After the introduction of the rupee, the British began issuing Javan rupee bank paper instead of Reals.

A shortage of copper currency was found; copper duits were produced in 1812 bearing the British East India Company’s mark ‘VEIC’, ‘JAVA’, and the date. A lack of raw copper led to an experiment with melted cannon; this succeeded only in destroying the dies. A request by Raffles to Calcutta mint to produce 50 million duits could not be met, and so the British produced 50 million tin duits in 1813 and 1814, at roughly half the weight of the copper duits. These coins were not widely accepted and over a million were returned, and on the return to Dutch control, the Dutch refused to recognise the coins.

Dutch rule was restored in 1814 as a result of the treaty between the Netherlands and Britain returning the former Dutch possessions. The first coins to be minted were at the Surabaya mint. There had long been a shortage of copper coinage in the Indies, and as a consequence Chinese and Japanese copper coins were in general circulation. French centime coins had been imported in 1811, but subsequently withdrawn; in 1818 to address the shortage, copper bonks were once again issued . Although 400,000 gulden-worth were produced, they had been severely debased at 15 g of copper to the stuiver, and they were eventually withdrawn in 1826. The first silver coinage minted for the colony were 99,000 gulden coins minted in Utrecht in 1821 and coins were finally fully decimalised in 1854. The new coinage bore Arabic script alongside Dutch language, which earlier Dutch-minted had not done and continued to be issued until 1945, with copper changing to bronze from 1914, the addition of silver gulden coins in 1943 and a copper-nickel 5 cent that issued in 1913, 1921 and 1922. No coins in any denomination were minted between 1861 and 1881. The last coins are dated 1941–1945 and were minted in the USA while the Dutch were tied up in World War II and the Japanese were ruling the Indies.

Due to a lack of bullion reserves, towards the end of the expiry of the first rights, ‘kopergeld’, or copper money notes, were issued. These were redeemable on the basis of ‘tegen honderd duiten de gulden’—or 100 duit to the gulden.

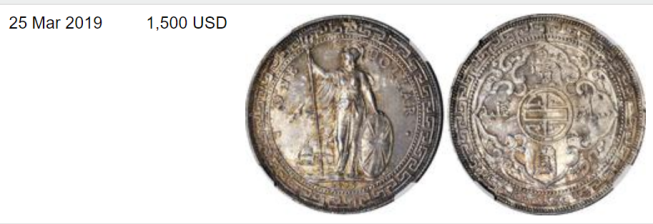

Straits Settlements

The first coins issued for the Straits Settlements in 1845 were copper. They were issued by the East India Company and did not bear any indication of where they were to be used. A second issue of the same denominations was produced in 1862 by the government of British India. These bore the inscription “India – Straits”. In 1871, silver coins were issued in the name of the Straits Settlements and silver dollars were first minted in 1903. A special issue of the Straits Settlements Government Gazette published in Singapore on 24 August 1904, contained the following proclamation by then Governor, Sir John Anderson:

From 31 August 1904, British, Mexican and Hong Kong Dollars would cease to be legal tender and would be replaced by the newly introduced Straits Settlements Dollar.

The purpose of this action was to create a separate exchange value for the new Straits dollar as compared with the other silver dollars that were circulating in the region, notably the British trade dollar.

The idea was that when the exchange value had diverged significantly from that of the other silver dollars, then the authorities would peg it to sterling at that value, hence putting the Straits Settlements unto the gold exchange standard. This pegging occurred when the Straits dollar reached the value of two shillings and four pence against sterling. Within a few years, the value of silver rose rapidly such as to make the silver value of the Straits dollar higher than its gold exchange value. To prevent these dollars from being melted down, a new smaller dollar was issued in 1907 with a reduced silver content. A parallel story occurred in the Philippines at the same time. Dollars were last struck for circulation in 1926, with 50 cents production ending in 1921. The remaining coins continued in production until 1935.

In 1942, the Japanese successfully invaded the Indies, bringing with their invasion fleet their own version of the gulden. Following the fall of Singapore into the hands of Imperial Japan, the Japanese introduced new currencies as a replacement of those previously in use in the occupied territories of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei.

The new currency in Malaya and Singapore were issued with the same value as the Malayan dollar, and first entered circulation in 1942. As with other currencies issued by Japan in occupied territories, local residents were forced to adopt this type of currency, while existing coins were allowed until a shortage of coins required the Japanese administration release issued notes for cents. Although new coins bearing the name “Malaysia” and dated under the Japanese calendar were planned by the Osaka Mint for the region, these never made it passed the concept stage and only a few rare patterns exist.

To supply the authorities with money whenever they required it, they simply printed more notes. This resulted in hyperinflation and a severe depreciation in value of the banana note. Moreover, counterfeiting was rampant due to its lack of a serial number on many notes. Increasing inflation coupled with Allied disruption of Japan’s economy forced the Japanese administration to issue banknotes of larger denominations and increase the amount of money in circulation.[Sharp drops in the currency’s value and increased price of goods frequently occurred following a Japanese defeat in battle abroad.

Different denominations of the banana money (top and left) on display at Memories at Old Ford Factory, Singapore. As banana money was rendered worthless immediately after World War II, banana money notes are now either museum exhibits or collectors’ items.

After the surrender of Japan, the currency became entirely worthless, and to this day the Japanese government has refused to exchange these currencies. Some locals managed to escape poverty because they had hidden Straits dollars and Malayan dollars, the previous currencies before the Japanese invaded. Those with hidden stashes of the old dollars were thus able to use them the moment the British resumed control of Singapore and surrounding colonies, when they became valid again. A number of surviving banknotes were stamped as war souvenirs, while its use as printing paper for rudimentary calendars for 1946 was also recorded. When these notes became obsolete, punch holes were made in the notes to indicate they had been “cancelled” and stripped of redeemable value.

By 1944 they had decided that engendering a collective Asian nationalism would be the key to keeping control, and they replaced the Dutch-style gulden notes by the Netherlands Indies roepiah, an Indonesian-language version of the gulden.

The Dutch government in exile ordered notes for issue on their return to Indonesia, and these were printed in the USA in 1942, dated 1943. They began to be issued in the eastern islands of the archipelago [which the Dutch captured early on] from 1944 to 1945. Because of Dutch fears about damage to De Javasche Bank from the war, they were issued under the authority of the Dutch government instead, hence they were known as the ‘NICA Gulden’ [Netherlands Indies Civil Administration gulden]. In Java and Sumatra, Indonesian nationalists were insurgent, and the Dutch were initially confined to only a few cities. In both islands the Japanese invasion money continued to circulate among both Indonesian and Dutch, until supplies ran out. The issue in 1946 of the first Indonesian rupiah by the provisional Republican government in Jakarta resulted in conflict between the rival currencies and administrations. The Dutch money was not tolerated by the Indonesian nationalists, who insisted on the use of only Indonesian money.

After 1946 De Javasche Bank resumed note production, with 5, 10 and 25 gulden notes. These bore in Indonesian language the word “roepiah”. The NICA gulden, on the other hand, bore the image of the Dutch Queen, and was far from sensitive to nationalist feeling. Further notes simply saying “Indonesia” were issued in 10 and 25 sen denominations in 1947.

In November 1949, peace was brokered. One of the conditions was that “De Javasche Bank” remained as the central bank of the new nation of “Republik Indonesia Serikat” [United States of Indonesia]. Thus the first internationally recognised currency of the new nation of Indonesia still bore the words “gulden”, and “De Javasche Bank”, reusing the 1946 De Javasche Bank notes, changing only the colour, and with additional denominations of 50, 100, 500 and 1000 gulden. Further De Javasche Bank notes, in a new design, were dated “1948”, with 1⁄2, 1 and 2 1⁄2 gulden denominations, and were also issued upon Indonesian independence, along with new ‘Republik Indonesia Serikat’ notes in 5 and 10 rupiah denominations. The feeling for “Indonesianization” was strong, and so De Javasche Bank was nationalized and renamed as “Bank Indonesia” over the period 1951 to 1953, and Bank Indonesia rupiah notes began to replace the gulden from 1953.

Netherlands Trading Society

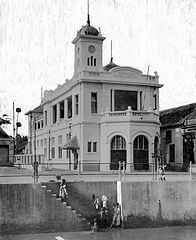

The NHM was a private company which issued publicly traded shares and according to the king, the NHM would act to leverage economic activity and encourage the development of national wealth. However, in practice it came down to expanding existing trade, by gathering data and searching for new markets as well as financing industry and shipping. Its close association with Dutch government meant it played an important role in the development of trade between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. Its former headquarters in De Bazel in Amsterdam houses the Amsterdam Archives today.

The NHM was a private company which issued publicly traded shares and according to the king, the NHM would act to leverage economic activity and encourage the development of national wealth. However, in practice it came down to expanding existing trade, by gathering data and searching for new markets as well as financing industry and shipping. Its close association with Dutch government meant it played an important role in the development of trade between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. Its former headquarters in De Bazel in Amsterdam houses the Amsterdam Archives today.

The NHM is sometimes called the successor of the Dutch East India Company, as it was also a private company that issued shares and financed trade with the Dutch East Indies. The establishment of the NHM could probably be seen as an attempt to bring new impetus to trade with the Dutch East Indies after the depression of the years of French domination from 1795–1814 and the final collapse of the VoC two decades earlier.

The NHM is sometimes called the successor of the Dutch East India Company, as it was also a private company that issued shares and financed trade with the Dutch East Indies. The establishment of the NHM could probably be seen as an attempt to bring new impetus to trade with the Dutch East Indies after the depression of the years of French domination from 1795–1814 and the final collapse of the VoC two decades earlier.

The NHM financing of trade and shipping led to the development of a network of branches which increasingly engaged in financing and banking operations. The network extended throughout South East Asia and on the trade routes between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies and the NHM continued to extend its network into the 20th century.

The NHM financing of trade and shipping led to the development of a network of branches which increasingly engaged in financing and banking operations. The network extended throughout South East Asia and on the trade routes between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies and the NHM continued to extend its network into the 20th century.

It lost a number of its branches when the Indonesian government nationalized them in 1960 to form a new  locally owned bank, but by then had branches in many other parts of the world. The NHM continued to developed more and more banking and financing operations with its branch network and it went on to become one of the primary ancestors of ABN AMRO bank when in 1964 it merged with the Dutch Twentsche Bank to form Algemene Bank Nederland (ABN).

locally owned bank, but by then had branches in many other parts of the world. The NHM continued to developed more and more banking and financing operations with its branch network and it went on to become one of the primary ancestors of ABN AMRO bank when in 1964 it merged with the Dutch Twentsche Bank to form Algemene Bank Nederland (ABN).